What is Prestige?

The highest possible compliment you could ever pay to a lie without going over the line and believing it.

I really like the word “prestige.” I find it extraordinarily helpful when it comes to organizing my own thoughts, but sometimes that causes hiccups in communication with others who use it differently than I do. Oxford defines prestige as “widespread respect and admiration felt for someone or something on the basis of a perception of their achievements and quality,” which sounds more positive than the way I usually mean it. “Widespread perception” is something I’m fundamentally wary of, so the word “prestige” always reads like a warning to me. It’s like how the term “viral” is sometimes attached to words like “success” or “popularity” in order to make them sound suspicious. Back in the seventeenth century, when the word “prestige” first caught on in the Anglosphere, it was actually being used in a very similar way.

In 1937, the British diplomat Harold Nicolson published a treatise on “The Meaning of Prestige” via The Atlantic that can help us understand the relevant historical context. “The word ‘prestige’ derives from the Latin verb praestringere as generally employed in the phrase praestringere oculos, ‘to bind or dazzle the eyes.’” he writes. “from this verb comes the even more disreputable substantive praestigia, which means nothing more or less than ‘juggler’s tricks.’” The word itself came to us from France, and Nicolson reminds us that in French classical literature, the word prestige “is invariably used with a lively sense of its disreputable origins.” A sense that is undiminished, he adds, by the similarity it bears to the word prestidigitateur, which means “magician.”

“To the French mind,” Nicolson writes. “the word prestige should sometimes carry with it associations of fraudulence. At its best, it conveys something akin to our own words ‘glamour’ and ‘romance.’ At its worst, it suggests the art of the illusionist, if not a deliberate desire to deceive.” As the word became popular in English-speaking countries, it “lost all association with jugglers or conjurers” and flattened into the one-dimensional shadow of itself described in the dictionary definition of the word today. I think that’s a shame. We could use a word that captures the experience of being impressed by something that you know for a fact is bullshit. A word that’s like, the highest possible compliment you could ever pay to a lie without going over the line and believing it.

The decade we all just lived through was a fever dream of rug pulls, juiced metrics, and false advertising that we’re all still struggling to piece together after the fact. The current decade threatens to take the failings of the last to wretched new extremes. As inflation wipes out the discretionary income of most working class people, corporations are scrambling to transform ordinary mass market products into “elevated,” “premium” “services” and “experiences” in order to maximize their appeal to the shrinking minority of people in this country that can still afford to self-identify as connoisseurs. The target audience for prestige as a concept is now indolent dilettantes who are rich enough to sign up for an annual subscription and then never think about it again. I think we used to call them “suckers.” If the cancerous multinationals that own everything have already decided that prestige means “things that are for suckers” now, maybe it’s time to reconsider the classical definition.

To illustrate what I mean, let’s use an example from the games industry. The Last of Us is a very well-known prestige video game that is on a lot of folks’ radar presently because it was adapted into a prestige television series for HBO. Such intense levels of prestige are unusual for any games-based intellectual property, perhaps owing to the catastrophic failure of past attempts to adapt marquee franchises like Super Mario Bros. and Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within. That makes it the perfect case study to help us understand how prestige functions in practical terms. We just have to ask the obvious questions: who owns this, and how is it making them money?

The answer to the first question is simple enough. The Last of Us was created by Naughty Dog, a Santa-Monica based studio that Sony owns. Their purpose within the company is to drive sales of the PlayStation line of home consoles by developing exclusive games for the platform. First-party games of this nature are explicitly meant to demonstrate the console’s technical capabilities to the consumer, so budgets permit developers to be expressive in ways that the models powering third-party games rarely allow. First impressions are critical, and long-tail monetization is rare.1 It isn’t the consoles themselves that drive profits for Sony, though. The fifth-generation PlayStation hardware that Naughty Dog’s contemporary output exists to promote sold at a loss for almost a year. It may look like a hardware product, but PlayStation is actually a services platform.

Sony’s gaming business makes money by functioning as a landlord, taking a cut of every physical game purchase and thirty percent of the proceeds from every transaction that occurs digitally on the PlayStation store. The bespoke, self-contained narrative experiences that Sony’s first-party studios specialize in are often successful games in their own right, but not in any way that compares to the kind of money that Sony makes by laying back and taking a commission every time someone buys a bundle of in-game currency for an addictive time sink like Grand Theft Auto Online or NBA 2K23. First-party showpieces like The Last of Us or God of War are like exposed brick walls and claw-foot tubs; trendy, attention-grabbing details that a slumlord can use to distract from the black mold in the walls and the water spots on the ceiling.

With one hand, Sony is able to “bind or dazzle the eyes” with sophisticated prestige titles that are purpose-built to shatter negative preconceptions about the medium. With the other, they collect nearly a third of all the money being generated by all of the games on their platform that most aggressively confirm said preconceptions. Players who enjoyed God of War: Ragnarok, the company’s latest first-party success story, will quickly find themselves inundated with ads for Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, a superficially similar-looking title with a comparable Nordic theme. Both games cost seventy dollars in their base versions, but Valhalla wasn’t developed by one of Sony’s first-party studios. Valhalla needs to turn a profit in order to justify itself, which is a pressure that shapes game design at every level. The problem isn’t just that modern big budget third-party games are more likely to make use of predatory monetization tactics like loot boxes, gacha pulls, battle passes, and pay-to-win gameplay boosters. The problem is that these games are precision-engineered to feel empty without them.

Ragnarok’s plotting and level design are tight, focused, and respectful of the player’s time. Valhalla’s environments are as sprawling as they are monotonous, and the turgid narrative requires over a hundred hours of gameplay and a handful of paid expansions to conclude. One game is designed to make you feel good about the five hundred dollar machine you just bought, while the other is designed to make it seem like the seventy dollars you’ve already spent was wasted unless you’re willing to cough up another twenty. One game defines the PlayStation brand in the minds of consumers, the other one is what actually allows Sony to make money. In this context, “prestige” is an idealized, fantastical vision of what big-budget games could be that exists to make you vulnerable to the tedious reality of what they actually are.

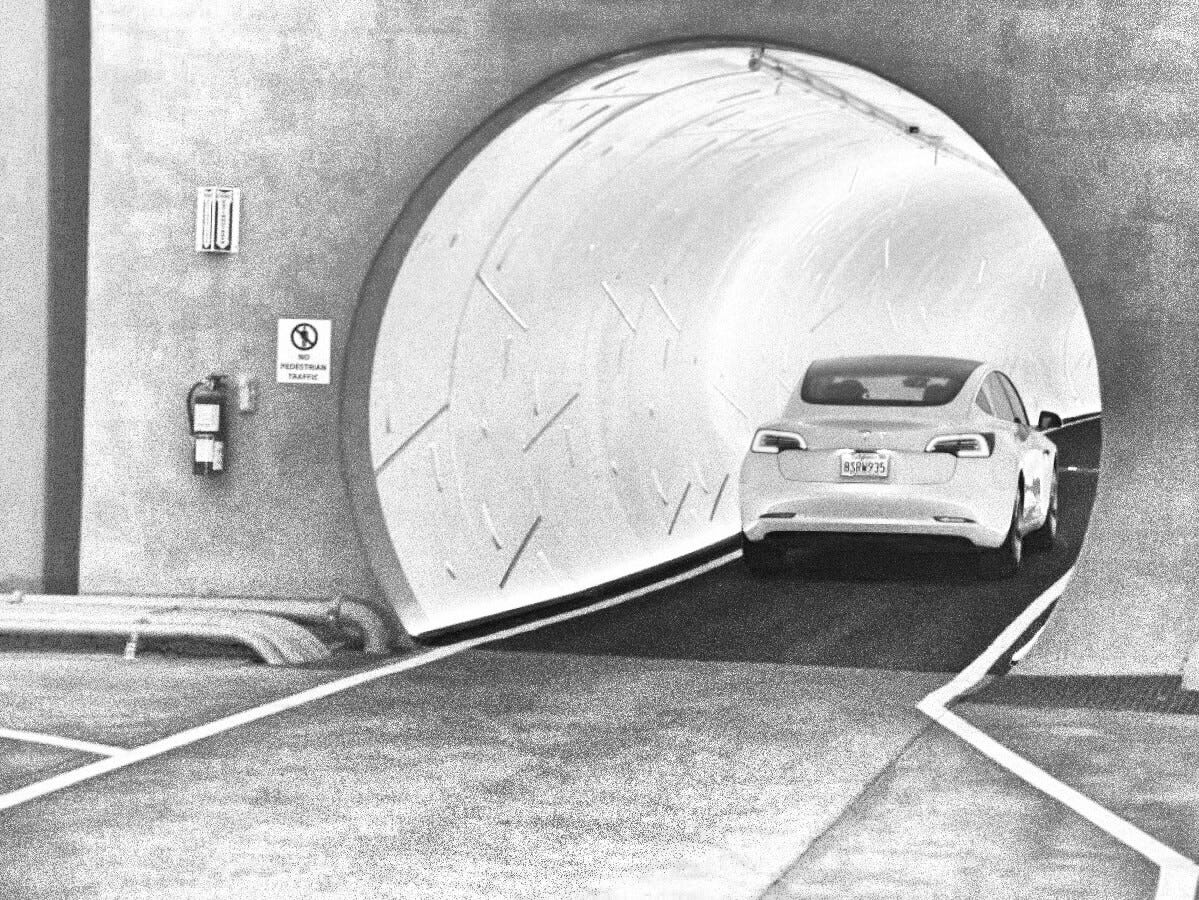

Have you ever seen any of those old Looney Tunes shorts where Wile E. Coyote paints a tunnel on the side of a mountain in order to trick the Road Runner into crashing into it? To me, that painted tunnel is like prestige. The craftsmanship might be exquisite, but it exists to mislead everyone who engages with it. Historically, the Road Runner is able to overcome the deception by entering the painting as if it were any other tunnel and continuing on as it had been. If contemporary prestige merchants like Sony or HBO were put in the coyote’s position, they’d likely determine that the painted tunnel is technically their intellectual property and find some way to force the Road Runner to pay a fee for all the time it spends running around in there.

When I look around, I wonder if this is already how others are using the word. When the films that dominate awards season conversations about the health of the medium are described as prestige products, is that an acknowledgement of the fact that they make basically no money and bear very little resemblance to the features that most of the world’s theatergoers are paying to watch? When the Grammys are described as music’s most prestigious award show, is that just a polite way of acknowledging that the awards are meaningless and the telecast is unpopular? Did we grow up subconsciously associating the word with “jugglers and conjurers,” or did we start doing that more recently, as a response to everything modern-day prestidigitateurs are doing to undermine our relationship with reality? What was going on in France during the seventeenth century, anyway? Do you think it might be relevant to our current predicament in some way?

I ultimately can’t speak to whatever the mainstream view is. I don’t live there. “Widespread respect and admiration” for a thing on the basis of a “perception of achievements or quality” basically just tells me that I should only ever handle that thing with rubber gloves. The internet is optimized for addiction, whether it’s addiction to passive algorithmic consumption or to reactionary outrage against against the viewpoints of strangers. Perception is a constant battleground, where billions of dollars are spent daily to perpetuate the idea that a premium surcharge can make up the difference between a good life and a bad one. What’s the point of a word that straightforwardly means “things that are supposed to be good” in this economy? Nothing is what it’s supposed to be anymore. The “disreputable origins” of the word prestige are a much better fit for these times.

Though it’s true that first-party games are rarely monetized as aggressively as third-party titles, (hard to make the customers feel like the console was a good value for money when the flagship showpiece that got them to take the plunge is constantly hawking in-game purchases) the deeply resilient prestigiousness of The Last of Us seems to have presented an opportunity Sony couldn’t bear to pass up. Naughty Dog is currently developing a “multiplayer live-service game” set in the TLoU universe that Variety expects to include “microtransactions.”