The Base Determines The Superstructure

A story about songs that predicted the future, and what we can learn from them.

In the closing months of the twentieth century, a song called “Livin’ La Vida Loca” by Ricky Martin climbed to the top of Billboard’s Hot 100 singles chart and stayed there for five weeks. The track’s mainstream success was hailed as a significant commercial breakthrough for Latin music, and indeed, it certainly was followed by several English-language crossover hits by other established Spanish-language artists like Shakira and Marc Anthony. For a time, it seemed like the biggest names in the growing Latin music industry were being given the opportunity to transcend it.

Though the Latin explosion was extremely visible and highly discussed back then, the ongoing difficulties that contemporary artists continue to have getting songs with Spanish or Portuguese lyrics played on American radio stations receive comparatively less attention. By most metrics, the Puerto Rican rapper and reggaetonero Bad Bunny was the biggest artist of last year. He had the biggest album, the biggest tour, and the biggest streaming presence. On radio, however, he was a complete non-entity. More than two decades after Ricky Martin’s crossover moment, Spanish-language hits like “Despacito” and “Mi Gente” are still only ever permitted to receive airplay when amended by English-language verses from artists that the hyper-consolidated American radio landscape is already comfortable with.

“Livin’ La Vida Loca” itself was written by Desmond Child, a veteran arena rock hitmaker known for penning successful crossover efforts like “Dude (Looks Like A Lady)” by Aerosmith and “You Give Love a Bad Name” by Bon Jovi. His team cited the Pulp Fiction soundtrack and the music of Frank Sinatra, who had passed away not long before sessions began, as their primary musical influences. The song’s mixing engineer Charles Dye even acknowledged in an interview that he was asked to “tone down” some of the “Latin elements” in the production by Martin’s label. “There are some songs on [the album] that wear their Latin nature on their sleeve,” he said. “But that’s not really the case with ‘La Vida.’ It’s designed to move Ricky into the mainstream.” The song’s runaway success, then, was less a breakthrough for Latin music than an opportunity for a handful of Latin artists to make conventional pop hits. Whatever doors it opened did not seem to stay that way for long.

It was the late nineties, after all: the undisputed zenith of the CD era and, by some metrics, the peak of the entire American record industry itself. There was no need for a musical revolution in the record business: the status quo was working as well as it ever has. Manufactured pop groups were breaking sales records that have yet to be surpassed, and formerly niche local scenes comprised of New York street rappers and Bakersfield groove metal bands had been successfully refashioned by labels into Motown-style hit factories. The major labels’ enthusiasm for Latin artists was not too different from their interest in the independent Michigan horrorcore outfit Insane Clown Posse1. They weren’t looking for a paradigm shift so much as new ways to sell middle-of-the-road pop and rock records to the dwindling minority of consumers that weren’t already buying them. It was the dot-com bubble, an era of reckless imperial expansion. The goal was to collapse every niche they didn’t already own into the monoculture.

At the start of the twentieth century, the music industry revolved around publishing. Sheet music sold better than recordings, and so recordings did not define songs in the mind of the listener. Friends and family would cluster around the piano to sing the popular tunes of the day together, and in the absence of modern amplification, live music revolved around large bands playing a wide variety of tunes rather than individual artists performing their own material. To fill up a crowded ballroom with sound, you needed a critical mass of horn players. Most of the hit songs these “big bands” played were written by full-time professionals working nine-to-five jobs at New York-based music publishers2. Those were the songs that everyone knew, and so those were the songs that audiences expected to hear at concerts regardless of who was onstage. Every great band was effectively a wedding band, and every great musician who made their mark on the times back then had to figure out how to do it within that context. Chuck Berry was having none of it.

When he scored his first hit single with “Maybellene” in nineteen fifty-five, modern vinyl records had only recently replaced brittle pre-war shellac as the record industry’s format of choice. This made it possible for prerecorded music to finally displace live performance as the dominant form of music heard on radio broadcasts3. The publishing-era practice of having hit songs recorded by dozens of artists was still standard operating procedure on the label side, but audiences had started to care much more about hearing the one “definitive” recorded version of their favorite songs. In the golden age of Tin Pan Alley, a songwriter created a hit by coming up with something that millions of people could imagine themselves singing—something like “Take Me Out To The Ball Game” or “Happy Birthday.” Making a hit record, on the other hand, required Chuck Berry to come up with something that nobody could imagine being performed by anybody but him. That’s exactly what he did.

Billboard’s main singles chart back in fifty-five was called the “Honor Roll of Hits,” and it differed from contemporary charts in that it had to specify which of the many available recordings of a particular song was selling the most copies. When a new song from any source hit the charts, it kicked off what the trades would often call a “sweepstakes” that only one record could win. In October of that year, Berry succeeded in overtaking a crowded field of competitors to become the first Black rock and roll artist ever to have the best-selling version of their own chart hit. This was a stunning accomplishment. Even Hank Williams, one of the most impactful singer/songwriters in the history of the craft, experienced the only mainstream crossover success of his lifetime when Tony Bennett cut a lavishly arranged cover version of “Cold, Cold Heart.”

It wasn’t just that Berry had to overcome American broadcast media’s insidious preference for sanitized cover versions of Black rhythm and blues hits—he had to compete with a landscape of professional songwriters and performers that were used to creating music in a completely different way. He had to demonstrate to the audience that was buying up truckloads of nostalgic, family-friendly product like “The Yellow Rose of Texas” and “Bible Tells Me So” that a different world was not just possible, but desirable.

With “Maybellene,” Berry had arrived just in time for the beginning of a new era in music. One that his very specific skill set turned out to be ideally suited for: he wrote the songs, played the lead instrument, and choreographed his own stage show. A job that once required a crack team of performers, arrangers, and songwriters could now be done beautifully by one guy if you plugged him into a large enough amplifier. He even refused to tour with backing musicians, on the basis of his contention that it wouldn’t make sense to pay anyone to learn his music because every rock musician on the planet already knew it from his records. For decades, he would just show up to the venue on his own and play with whatever local rhythm section could be assembled on short notice. There had never been anyone like him before, because there simply couldn’t have been. We didn’t have the technology.

The economic implications were significant, and not just for publishers. Feeding, lodging, and transporting large bands was expensive even before you got into the tricky business of compensating them fairly for their labor. Once smaller “combos” consisting of only a few members were able to sell a comparable number of concert tickets playing electrified rhythm and blues, the ongoing existence of the larger ensembles became difficult to justify financially. The continued popularity of wedding bands suggests the audience never fully lost their taste for that sort of entertainment, but the prohibitively high cost of booking them means most people will only ever attempt to do it once in a lifetime. The massive paradigm shift that collapsed the roles of singer, songwriter, bandleader, and soloist into one person was so heavily favored by the underlying economic conditions that it likely would have happened regardless of whether or not the masses liked the music.

Consider how hard the establishment tried to kill rock and roll after it first exploded in the fifties. The term “rock and roll” itself was popularized by Alan Freed, a radio DJ who rose to national prominence after the Black rhythm and blues records he played on his show started to resonate with a teenage audience. He was the opening through which the music first infiltrated the nation’s heavily gate-kept radio ecosystem, so the authorities came down on him very hard. Police started shutting down the wildly popular concerts he was organizing, prompting him to quit his job in protest. Congress opened an investigation into the practice of “payola,” suddenly developing a powerful interest in the curatorial practices of radio DJs at the exact moment in history where some of them started playing records by Black musicians. Freed was fired from a different gig in fifty-nine after having been uncooperative in his testimony before a Senate committee, and subsequently drank himself to death in relative obscurity six years later.

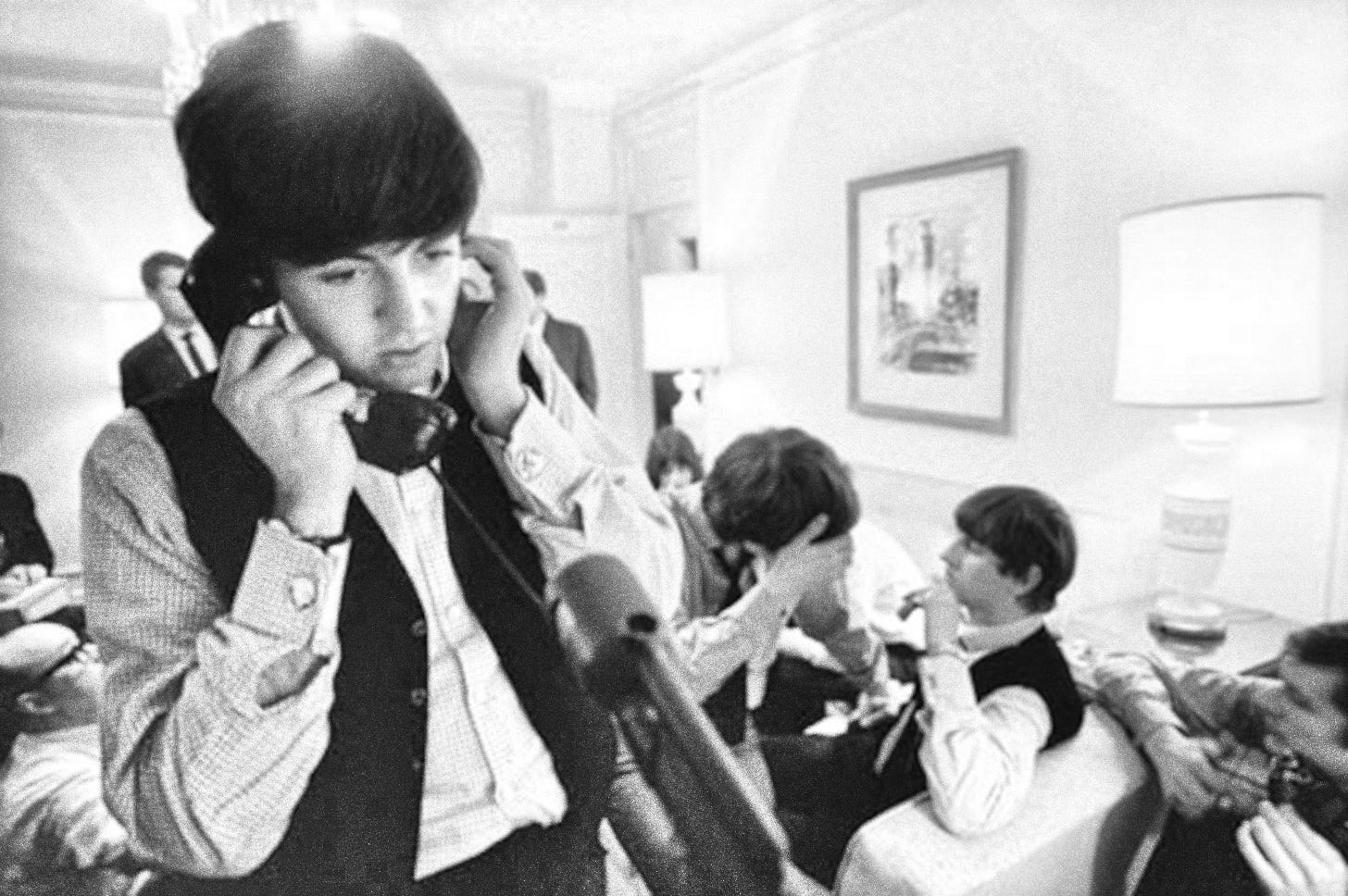

By the end of the fifties, the rebellion seemed to have been put down. Elvis Presley had been drafted into the army and shipped off to Germany, a conspicuous occurrence given that it was peacetime. Little Richard had abruptly retired from secular music after seeing the Russian satellite Sputnik-1 streaking across the sky from an airplane window and interpreting it as a sign from God that he should rededicate himself to religion. Berry himself was arrested in fifty-nine for transporting a minor across state lines and sentenced to five years in prison. Critics of rock and roll, who derided it as a fad genre and claimed that the music’s popularity had been artificially inflated by bribes from record companies, had reason to believe their perspective had been vindicated. When the Beatles arrived in America for the first time some years later, they were horrified to find that their beloved rhythm and blues had no presence in the mainstream. Aghast, they spent hours calling up radio DJs from their hotel room and requesting all of their favorite records. Most of the teenagers listening at home were probably hearing that music for the first time.

Today, the bite-sized dark age that separated the initial fifties outbreak of rock and roll from Beatlemania looks like little more than a blip in retrospect. The most successful artists of the decades that followed, by the numbers, were those that viewed Chuck Berry as a blueprint rather than a cautionary tale. The Rolling Stones’ first single was a Chuck Berry cover. The Beach Boys’ first hit was a Weird Al-style rewrite of “Sweet Little Sixteen” that changed the lyrics to be about surfing. The Beatles themselves covered “Rock and Roll Music” at every concert they played from their EMI debut until their retirement from touring, almost as if they considered the song to be a required prerequisite for appreciating the original songs that followed. Despite emphatic support from esteemed Columbia Records A&R man John Hammond, Bob Dylan struggled to crack the mainstream until he threw out Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music and started following Berry’s example by writing his own tunes and playing them with an electric band. “Tin Pan Alley is gone,” he would later proclaim. “I put an end to it. People can record their own songs now.”

Many contemporary artists also seem to exist firmly within Berry’s lineage. Autobiographical story-songs like “Johnny B. Goode” established a template that Taylor Swift’s biggest hits have all utilized to dazzling effect. The Weeknd’s Abel Tesfaye essentially headlined Coachella alone last year, making the case that one guy performing his own material can still outshine teams of elite professionals if you plug him into a big enough amplifier4. The artist who reminds me of Berry the most, though, is Kanye West. Both were midwestern eccentrics who saw themselves as genius auteurs, and managed for a time to convince the mass audience to see them similarly. The “millenial whoop” first heard by a generation of producers on Graduation and the distorted 808 bass drum popularized by Yeezus are two of the only sounds in the recent history of American popular music to become anywhere near as ubiquitous as Berry’s distinctive guitar soloing once was. Both achieved success by being early adopters of new technology that would go on to change music forever, and both left an indelible imprint on every young artist who first came to understand the potential of that technology through them.

Whenever new technology impacts the music business, there’s always talk of how it will “democratize” music and open up new “creative possibilities.” In the case of Chuck Berry, this is demonstrably exactly what happened. Amplified guitars, magnetic recording tape, and resilient vinyl discs allowed him to make music that couldn’t have existed otherwise, and to experience a level of success that would not have been possible ten years earlier. Still, the underlying economic conditions and incentive structures of our society can only allow for so much possibility. It may be true that Berry blazed the trail that the world’s most successful recording artists have been walking ever since, but maybe the scope of what’s possible in our world is too narrow to accommodate any other way of doing things. Maybe the frontier wasn’t wide enough for more than one trail in the first place.

Amidst all the hubbub about the Latin explosion, there was another side to the story of “Livin’ La Vida Loca” that did not entirely escape national notice. In November of ninety-nine, the New York Times ran a piece called “Technology Puts the Recording Studio on a Hard Drive” as part of their now-defunct tech-focused “Downtime” column. “Like many featherweight chart-toppers of summers past, Ricky Martin’s ‘Livin’ La Vida Loca’ may soon be blown into the remainder bin,” it began. “But the song is assured of at least a small place in technological history. On May fifteenth, [the song] became Billboard’s first number one single to have been recorded and mixed entirely using a computer. Instead of building up the music track by track on a tape-based analog or digital multitrack recorder, one of the album’s producers, Desmond Child, used a powerful computer system called Pro Tools to record all of the song’s vocals and backing instruments directly onto a series of massive hard drives.”

When Desmond Child first built his cutting-edge, digital-first Miami recording studio in the mid-nineties, what he was doing was fairly unusual. Professional songwriters didn’t typically meddle in production even before authenticity replaced showmanship as the coin of the realm in ninety-two. Back then, the glammy slapstick and vaudevillian razzle-dazzle of eighties arena rock had given way to a gritty, no-frills ethos inherited from hardcore punk. Grunge bands were focused on the creative possibilities afforded by dropped tunings and elaborate pedalboards, not computers and co-writes with the guy who helped Kiss make their disco crossover single. Well after the concept of “alternative music” took off, Desmond Child was still making the kind of music that most people seemed to be looking for an alternative to.

Pro Tools allowed him to double down and become a “producer” himself. His new studio allowed him to create demos that sounded exactly the way he wanted them to, negating the need to find points of commonality with a rock landscape that had become increasingly hostile to him. He christened it “The Gentleman’s Club” at a time when the world’s biggest rock stars were staging dramatic public protests in support of abortion rights and hanging out with Kathleen Hanna. Like Chuck Berry in the early fifties, Child looked superficially out of step with the industry around him. When he got Ricky Martin to number one, though, the narrative shifted. A task that once required teamwork, specialist knowledge, and professional craftsmanship could now be done by one early adopter in pyjamas if you plugged him into a sufficiently powerful computer. The frontier somehow got even narrower.

Six years later, the market for CDs was in free-fall. The excessive price-gouging that plagued the format in the nineties had pushed consumers towards alternatives. Some gravitated towards the resurgent vinyl format favored by prestigious indie labels, and others found sanctuary in the file-sharing ecosystem that was flourishing online. Video games also achieved a high level of mainstream cultural penetration, spawning distinctive subcultures including entire music scenes dedicated to remixing video game music and repurposing old consoles as instruments. The major labels experienced devastating losses after consecutive decades of continuous growth and started cutting spending in response. MTV found it difficult to retain viewers by showing the cheaper, lower-effort music videos that tighter label budgets were yielding, so they switched to the next-cheapest programming option and re-oriented their schedule around Ridiculousness, a show where VJs watch viral YouTube videos together and riff on them. The imperial excess of the Y2K-era music industry imploded, leaving behind a confused mess of conflicting priorities and an aesthetic defined by unconvincingly yassified austerity.

The sky was the limit. Now, it was falling. The industry’s business model was going the way of Icarus, but one veteran opted to base his around Prometheus instead. His name was Charles Dye, and he was the mixing engineer who helped “Livin’ La Vida Loca” become the first digitally mixed Billboard number one ever back in ninety-nine. In two thousand and five, he made a much deeper and more lasting contribution to American popular music. He released an instructional film about mixing in the digital domain as a DVD you could order online. He called it Mix it Like a Record, and users of a popular internet forum for audio engineers hailed the film as “a massive knowledge transfer” which made it “a steal” at the eye-catching price tag of one hundred and fifty US dollars5. It offered practical advice about working with specific programs and plug-ins derived from years of hands-on experience, but also philosophical musings about how to make sense of the capabilities of the software without getting overwhelmed.

The film arrived at the perfect time. The record industry needed cheaper content, and the MSRP of an Apple PowerBook G4 was much lower than the cost of building a traditional recording studio. Dye’s expertise proved invaluable to anyone who wanted to learn how to turn digital demos into saleable products, whether they were using Pro Tools or accessible alternatives like GarageBand or FL Studio. A generation of autodidactic would-be Desmond Childs was trying to build the future of the music business on a rickety foundation of intuition, pirated software, and cheap consumer electronics. In Dye, they had found had a mentor with unimpeachable credentials and a keen sense of his target audience’s needs. Whether the viewer was a novice who required an overview of basic concepts or a journeyman who needed the opportunity to look over an experienced engineer’s shoulder while they work in order to grasp more advanced techniques, he had them covered.

To most people, Mix it Like a Record would make for fairly tedious viewing experience, but for a certain type of person it was basically the Rosetta Stone. Watching it now can feel like seeing one of those YouTube videos that demonstrate how many Y2K-era rap beats were based around Korg Triton presets, or discovering The Fall and realizing that James Murphy has just been doing an impression of Mark E. Smith this whole time. If you weren’t there, you can’t help but see the work through the prism of all the better-known things it influenced. Like the British youths that used theatrical rock and roll films from America like “Rock, Rock, Rock” and “The Girl Can’t Help It” as the blueprint for the their mid-sixties “invasion,” Dye’s apprentices went on to inaugurate a new era in music. The reign of guitar-toting singer/songwriters drew to a close, and the age of laptop-wielding producer/artists began to arrive in earnest.

The economic implications were significant, and the artists who experienced the greatest success in the years that followed were those who understood that. The conventional industry wisdom about rap records in the aughts, for example, is that they needed melodic choruses performed by pop or R&B singers to become hits. By using pitch correction software to become his own hook singer, Drake successfully collapsed multiple skill sets into one and established a template that countless mainstream stars have been building on ever since. Hybrid DJ/producer/artist brands who commissioned elaborate prerecorded audiovisual live sets based around their own material became much bigger live draws than most bands. Some of those producers found ways to streamline their business models even further by writing their own topline melodies, like Calvin Harris does, or by transforming fully into a featured performer on their own tracks like the Chainsmokers’ Drew Taggart.

Even experimental acts on independent labels, a class of artist that once existed solely to provide an alternative to mainstream pop for erudite record collectors, spent the bulk of the twenty tens trying to convince audiences (or perhaps themselves) that they could make Billboard chart hits too. The one that came the closest to realizing this ambition was probably Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker, a veteran of Australia’s Modular Recordings who made a name for himself by figuring out how to create lush, textured psych-rock records by himself on a computer. His profile in America rose substantially after his music became popular with rappers and pop stars; peers who recognized him as a fellow traveler in the new era of digital production at a time when most of his audience still perceived Tame Impala as a conventional rock band. This success was a rare bright spot in what otherwise became a sprawling wasteland of ill-considered aesthetic revamps and failed crossover attempts by niche creators with no obvious constituency in the mainstream. The economic incentives to streamline and modernize were apparently difficult to resist even in the face of audience backlash.

Rock groups with four or five members once seemed positively spartan compared to the large dance bands of the jazz age that they replaced in the cultural firmament. Today, the staggeringly high cost of essential amenities like gas and rent have made the traditional rock band setup an uttainable luxury for many. The Asheville band Wednesday addressed this in a a viral thread about the economics of touring on Twitter last year, which prompted onlookers to berate them for considering hotel rooms an essential expense. Many insisted they were just spoiled brats who had fallen short of the shining example that the hardcore punk bands like those profiled in Michael Azzerad’s Our Band Could Be Your Life had provided back in the eighties. I wonder a lot about what the Minutemen’s D. Boon, that scene’s deepest and most empathetic thinker, would have said in response. None of us will ever know, because he died back in eighty-five. He was sleeping off a fever on the floor of a tour van when the rear axle snapped and sent him flying out the back door onto the highway.

Speaking to Mariana Timony for Bandcamp, Emma Maatman of the Los Angeles band Dummy responded to the controversy with her own thoughts about what it takes to make touring work as a proper band in current paradigm:

“[Bands] think they can post pictures on Instagram and people will think their band’s good and then they’ll get a PR person or whatever,” says Maatman. “And that does happen. But the way to guarantee that you can get to that stuff is if you just do it yourself. We happen to be a very lucky band in that we have somebody who has a lot of experience with being on tour, meeting bands, booking shows, doing PR. I’m an artist, I have connections. Everybody has their own specialization in our band. We didn’t have to learn to do certain things. We just had that.”

In other words, Dummy was able to succeed where so many other groups had floundered because their members have cultivated amongst themselves a very specific set of skills that allows them to function without requiring too much outside help. A fully self-contained indie band that comes bundled with an experienced publicist, booking agent, and tour manager has obvious advantages over groups that do nothing but play music. The strategy is to operate with low overhead, to refine your project until the margins are sleek and aerodynamic enough to fit through the applicable bottlenecks. The band’s ability to turn a profit on the road seems miraculous given the wasteland of misery and failure that the American touring landscape has become after COVID, but the methods are still basically triage. Optimization can stop the bleeding, but it can’t raise the dead.

The masses do love a resurrection story, though. Sales of physical formats like CDs and vinyl represent a mere single-digit percentage of overall music consumption, but a tiny, insignificant uptick can still ignite widespread proclamations that old things are about to come back and music is inevitably going to return to the way it was. I guess the easiest way to soothe misgivings about the direction the rest of the world is going is to convince yourself that the planet will automatically reset back to factory settings once enough time has passed. That every flower which has ever bloomed is somehow a perennial, and that whenever a moment seems to have ended, it is in actuality just waiting for the right person to come along and flip the record over on the turntable. When an expected second coming doesn’t arrive on schedule, flippant evangelists can just blame critics, social media, or “poptimism” rather than acknowledge the giant vortex we’re all being sucked into. It’s a comfortable position. Good way to avoid ever having to grieve.

In reality, the history of the record business is not a story about rejuvenating cycles of natural death and destined rebirth. It’s a story about old, outmoded tech companies chasing diminishing returns. The path we’re on is a spiral, not a circle, and it’s getting smaller and narrower as we get closer to the end. Whether or not a Chuck Berry or a Charles Dye can figure out how to make the new developments feel exciting has no bearing on whether or not they ultimately happen. The base determines the superstructure. The frontier is only ever as wide as our underlying economic system allows it to be.

Those who have benefitted the most from ours have already started the process of consolidating the shattered wreckage of our culture industries into the one singular, unified form factor they believe the future will have room for. It will collapse art, entertainment, pornography, social media, dating apps, and gambling into an endless “algorithmic” feed of low-effort, low-quality clickbait optimized for engagement at the cost of addiction. In the past, halting this kind of “progress” required a two year nationwide ban on recording organized by the American Federation of Musicians. Absent that kind of collective action, the people who own everything will keep dragging us towards the event horizon regardless of what we want. Any other story we tell ourselves about how this all works is just a coping strategy.

According to Violent J’s memoir, “Behind the Paint,” the New York label Jive Records signed ICP with no intention of promoting them outside their native Michigan. Self-taught experts in the art of independent promotion, the group sent old tour vans loaded up with posters and street teamers to cities around the country during release week only to find their major label debut wasn’t being stocked anywhere than their old independent releases weren’t already hitting. The label’s goal was apparently to claim a majority of the royalties being generated by one of the country’s biggest independent success stories, not to break them into the national market.

Most of these publishers were clustered together on a particular Manhattan city block that became popularly known as “Tin Pan Alley.” The noise being made by offices full of professional songwriters banging out chords on cheap upright pianos all day long sounded to some like pots and pans being bashed together, hence the name.

Radio broadcasts had to be live prior to the forties because there was no way of playing back prerecorded audio with passable sound quality until the advent of magnetic tape. The Nazis deployed this technology first, using an early reel-to-reel tape recorder called the Magnetophon to allow uninterrupted propaganda to be broadcast twenty-four hours a day during the second world war. A member of the United States Army’s Signal Corps seized two such devices in the field and brought them back to America, where they found their way into the hands of tech-savvy musicians like Bing Crosby and Les Paul.

This made for a fascinating contrast with Harry Styles’ headlining set two nights earlier, which featured all the bells and whistles and guests and costumes and charming onstage interactions between performers you could ask for from a big festival show but was otherwise hampered by a catalog of tedious, forgettable songwriting. It was a plausible facsimile of a rock concert in much the same way that a block of ChatGPT text can seem like a plausible facsimile of academic research until you actually look up the citations.

The available evidence suggests this wasn’t just empty hype. MiLaR’s original DVD release offered buyers a lifetime of access to the film. Today, the only legal, reliable way to watch it is to rent access to the “remastered edition” for thirty dollars a month.