I: EXIT THE CRACKERVERSE

My official nationality is “Canadian-American.” That means I was born and raised in Canada, but I’ve spent most of my life living in the United States. This experience has given me a particular, distinct perspective on media.

The vast majority of all Canadians live within one hundred and fifty miles of the United States, which makes the border very accessible not just by car, but by antenna. During my childhood, every radio and television set I had access to could pick up just as many American stations as Canadian ones. Being able to flip back and forth between them at will was like being able to deliberately shift between two very slightly different realities. Over time, I started to get better at noticing what made each one distinct from the other.

Noticing those kinds of details is kind of a classic Canadian trait, I think. We all grow up being told that being Canadian is an essential component of our identities, but in order to develop any understanding of what the word “Canadian” is actually supposed to mean, we have to wade through the unrelenting torrent of American, British, and French cultural products that surrounds us at all times. We must all puzzle out for ourselves the reasons why America had to fight a revolution against Britain and we didn’t, or why the Québécois go to all the trouble of saying “chien chaud” when the French are perfectly happy to say “hot-dog.”

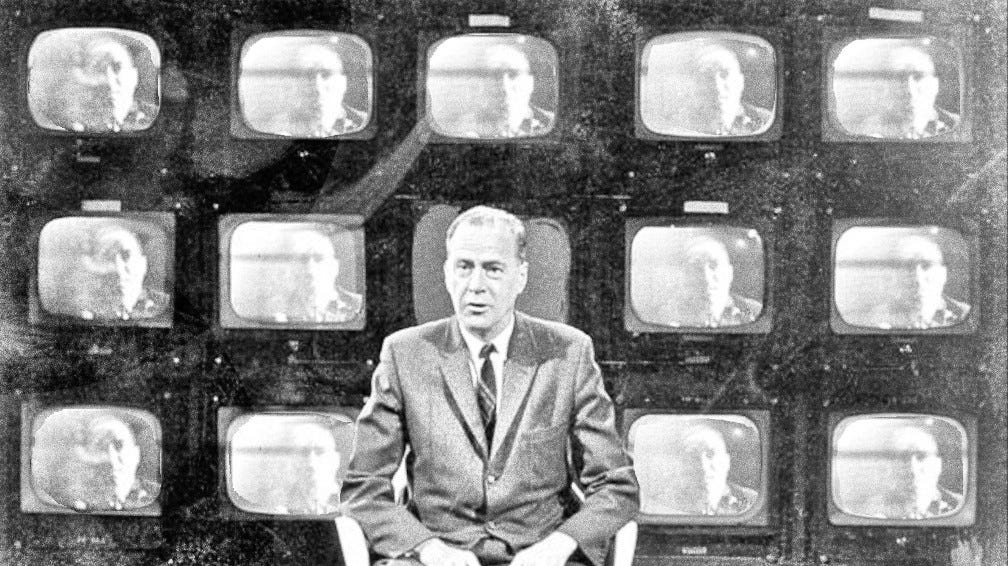

I think that’s how you get someone like Marshall McLuhan. Maybe experiencing television for the first time in a place like Toronto, where he could pick up both Canadian and American broadcasts, helped him to perceive the impact that the medium of television itself has, regardless of the the content of the programming. Maybe there’s something about the particular position that Canada occupies in the anglosphere that encourages this kind of thinking.

Another iconic Canadian is Drake, a perennial outsider that obsesses over regional rap scenes in America and Britain with the zeal of a Discogs power-user who wields unlimited disposable income. As the internet made the world a smaller, more interconnected place in the twenty tens, Drake’s popularity soared as he brought multiple scenes and sounds together under one transatlanticist umbrella. Now, at a time when the U.S. is shifting towards protectionism and geopolitical isolation, former collaborators from America are citing the exact characteristics that once made him so successful in their efforts to brand him as a colonizer, mirroring the rhetoric that President Trump recently used to justify a blanket twenty-five percent tariff on Canadian imports.

There’s also the comedian Mike Myers, who has achieved full-spectrum pop culture dominance playing characters based on his observations about other denizens of the anglosphere. One was Wayne Campbell, an American teenager who was obsessed with British rock bands. Another was Austin Powers, a British hipster from the post-war era who was obsessed with American hitmakers like Quincy Jones and Burt Bacharach. Even children theoretically know Myers for being the voice of Shrek, but he isn’t much of a celebrity in his own right. He was standing right next to Kanye West when he said “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people” during a Hurricane Katrina telethon, and barely anyone remembers seeing him. While some celebrities can rely on parasocial attachment to get over, Myers can’t count on the public’s feelings about him to put asses in seats. He’s a caricature artist who only wins when he gets the details right. Classically Canadian.

I think that Canadians are incentivized to get really good at noticing weird little details no one else cares about because, geopolitically speaking, Canada itself is a weird little detail that no one else cares about. Sometimes, if we work really hard, we can even convince the rest of the world that these details matter.

The most obvious way that Canadian media is different from American media is the existence of Canadian Content rules, colloquially known as CanCon. Canadian radio stations, for example, are legally required to devote a percentage of airtime to Canadian music. The standard number is forty percent, though some stations are allowed to get away with less than that depending on when they were licensed and what kind of music they play.

Once, in about nineteen ninety-seven, I was listening to a Canadian hard rock station in my home province of British Columbia. Nu-metal was ascendant back then, but this station wasn’t playing much of it. Their programming was a mix of reheated classic rock staples and lukewarm nineties alternative. As far as new music went, they were much more interested in playing a song called “Joining You” by Alanis Morrissette. It was the most guitar-heavy song on her new album, but Alanis was a pop artist who was already getting tons of airplay on pop stations for the album’s actual single, “Thank U.” Hearing “Joining You” over and over started to grate on listeners who tuned in hoping to hear the heavier sounds that were catching on in America.

“Why are you playing Alanis Morrissette all the time and not new bands like Coal Chamber?” one listener called in to ask. I remember the DJ sounding exasperated as he responded, insisting that he would love to play those bands but couldn’t, because none of them were Canadian. The problem was not him, or station management, but the requirement to devote forty percent of airtime to Canadian music. If his sets were boring, it was because Canadian music was boring. I got the sense that in an unregulated, fully market-driven ecosystem, this particular station wouldn’t have been playing much Canadian music at all.

It was a strange dynamic to try to comprehend. The listener didn’t seem to want the CanCon rules, and the DJ didn’t enjoy following them. Alanis herself was an established global celebrity working primarily in a different radio format. It would have been difficult to make the argument that support from hard rock stations was making much of an impact on her overall career. Who were these rules for, then? What good were they doing?

In the years that followed, my family moved to the United States, and I became a dual citizen. I left home, made my way to the nearest city, and started producing music myself. Eventually, after forming a band and posting some songs online, I experienced success. Throughout that whole period, my Canadian citizenship had been a complete afterthought. No one ever told me I looked or sounded Canadian, and if the subject ever came up in conversation, no one seemed particularly bothered about it either way.

Once I got to the point where I was dealing with record labels and booking agents, though, my citizenship suddenly mattered a great deal. I was technically a Canadian musician, which meant that CanCon rules existed for my benefit. It turned out that I was the reason why Alanis had to get played all the time on hard rock stations in the nineties. She had been holding a door open so that I might one day be able to walk through it.

I quickly learned a lot about different policies that the Canadian government employed to help Canadian artists. The first time I ever saw an iPad in real life was in the hands of a Canadian friend who came through my city on tour. The band successfully applied for a grant to fund the tour and used some of the proceeds to buy the iPad as an organizational tool. Grants could also be used to help pay for music videos, or any number of other creative or promotional expenses. So many of the people people I met in the industry, upon learning about my citizenship, excitedly shared with me their ideas about how I could use it to get money from the Canadian government. “I love working with Canadians” was a phrase I heard often.

In the end, I didn’t personally pursue any of those opportunities. I felt reasonably at home in the wild west era of MP3 file-sharing, but I never really acclimated to the more traditional businesses of playing shows and selling records. I lacked the confidence to operate effectively as a small business owner, which is what recording artists are before anything else. The knowledge that these programs existed did change my relationship with music forever, though.

Now, I can’t look at the sprawling lineups of aughts-era Canadian indie bands like the Arcade Fire and Broken Social Scene without wondering if the government was paying for all those extra floor toms and hotel rooms. I couldn’t listen to Chappell Roan’s impassioned speech at the Grammys about how labels should provide artists with health care without thinking about how artists from Canada wouldn’t need that benefit because they already receive health care from the government. I can’t help but roll my eyes when I hear one of the big indie success stories of that era, a fair number of whom hailed from countries with with even more robust social programs than Canada, credit “blogs” for helping them break through.

A common complaint you hear about record companies these days is that they don’t do “artist development” anymore. That labels expect success to happen instantly, and aren’t willing to put in the work required to properly realize the potential of the artists they sign. I think this is because labels have learned to outsource that work. If they want young artists who already have first-hand experience being on camera, they sign former child stars from the world of film and television. People like Ariana Grande, Britney Spears, Justin Timberlake, Sabrina Carpenter, and Drake. If they want young producers and songwriters who already have a lot of professional-grade experience and training, they look to countries where “artist development” is something the state helps pay for.

That might mean Canadian grants and CanCon rules, it might mean the monopoly power that allowed John Peel to give a national platform to underground UK music scenes, or it might mean the Swedish “culture schools” that offer music education and hands-on experience with modern studio tools to anyone who wants it. Sometimes, the key thing might just be something as simple as health care.

Now, if you’re an American consumer, you don’t have much incentive to care about any of this. All of the music in question has been made for you, with your sensibilities in mind. What does it matter to you if we “lose recipes” at home if the overall number of options available to you remains the same? Endless consumer choice is the prize you won for being born in a country that doesn’t provide you with health care, higher education, or arts funding, right? The world is your supermarket, full of an endless array of constantly-refreshing options. You get to listen to whatever you want, whenever you want, however you want. Details about where the records came from and how they were made just bring unwelcome complexity into a process that is otherwise becoming increasingly frictionless.

Me, though? I can’t help but care about the details. I grew up hearing that’s where you have to look if you want to find God. Or the devil. Sometimes I get confused about which one I’m dealing with, which is my most American trait.

Recently, the United States government has taken an unusually hostile position towards Canada. A twenty-five percent tariff on all Canadian exports has been implemented, and former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has characterized the policy as part of a plan to annex Canada and bring it directly under American control. Trump himself has repeatedly suggested that Canada should relinquish sovereignty and become the 51st member of the United States. He seems as serious about escalating this conflict as he is about anything.

For smaller countries, tariffs are a way of protecting developing economies from bigger players. During the Cold War era, for example, the United States was more willing to allow high tariffs from other countries in order to enlist them as allies against communism. President Trump’s actions in the present day suggest he no longer thinks those deals further America’s interests.

In pop terms, it’s like this: Canadian Content rules exist to protect the Canadian music industry from international competition, ensuring that radio stations have to reserve a significant percentage of airtime for Canadian artists and labels. This ensures that someone like Tate McRae has room to build an audience at home even in the face of fierce international competition. What Trump is doing with the tariffs is sort of the economic version of what would happen if he started claiming that CanCon rules are unfair because they restrict American access to the Canadian audience. It’s as if he proposed retaliatory new “AmCon” rules that block other countries’ access to the American market as a way of punishing them.

From Canada’s perspective, this new aggressive posture couldn’t be happening at a worse time. The country was already in crisis. Last December, Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland abruptly resigned, citing policy disagreements with Trudeau. The move shook all of Canadian politics because Freeland had widely been seen as the brains behind Trudeau’s operation ever since he first became Prime Minister in twenty fifteen. Trudeau had the name and the face that the Liberal Party needed to win national elections, but Freeland was the one who had an actual plan to lead.

I met Trudeau once, really briefly in a backstage green room that had been set aside for him at a big concert. I looked awful and felt worse, but when it was my turn to shake his hand and engage in the ritual of introducing myself, he startled me a little when he looked me right in the eyes and said “good to see you.” I walked away feeling kind of impressed. He wasn’t pretending the meeting meant anything or that he’d remember anything about it once it was over, but he successfully made me feel like it was good that it happened. Ever since then, I make eye contact and say “good to see you” whenever I’m being introduced to someone I know I’m probably never going to see again. Trudeau has always been great at surface-level stuff like that. During Trump’s first term, I remember hearing American liberals openly yearn for a Leader with Trudeau’s good looks and unshakeable decorum, and I get it. I don’t think it actually matters, but he does seem to have those things.

Ultimately, though, even Trudeau’s party decided they couldn’t survive on decorum alone. When Chrystia Freeland resigned as Deputy Prime Minister in December, the rest of the Canadian government acted as if the country’s actual leader had just quit. No one had any intention of letting Trudeau, a lightweight dilettante who never would have been the Prime Minister to begin with if his name didn’t remind voters so much of his father, pretend that he had what it takes to lead the country without Freeland’s firm hand guiding him. That would be like letting Pinky rule the world without The Brain there to back him up.

Trudeau capitulated and signaled his intention to resign in January, kicking off a contest to replace him as the leader of the Liberal Party. Freeland put herself in the running almost immediately, but found it difficult to shake off the resentment voters feel towards the Trudeau government she helped run for so long. Mark Carney, a fresher face who gained a lead in the polls after a well-timed appearance with American comedian John Stewart on The Daily Show, easily routed Freeland.

Canada has become home to some of the most expensive housing in the world, and inequality has been spiraling out of control for years, leading many Canadians to blame immigrants and environmentalism. Voters seem to want change, and Carney hopes a fresh face will pacify voters and prevent them from switching to the Conservative party in the next general election at the end of April.

Under normal circumstances, Canadians would probably abandon the Liberal Party at the ballot box and elect a Trump-style right wing populist. President Trump’s aggressive rhetoric about annexing Canada has changed the situation somewhat, though. The Liberal Party, which has been playing hardball with Trump and calling for national unity in the wake of his threats, is now polling better than they ever have in history. The existing problems that led voters to turn against Trudeau in the first place are extremely serious and are not going away, but the popular view is becoming that all of Canada might have more pressing concerns now.

One idea the Liberal Party has about how to counter U.S. aggression involves forming closer ties, militarily and economically, with “like-minded” countries like Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. They even have a cool acronym for this proposed alliance picked out already: CANZUK. The anglosphere minus the United States, essentially. It’s not as punchy or imposing as BRICS, and the idea that these countries will find a way to thrive outside of the Bretton Woods system might be wishful thinking, but it’s a concept I enjoy having an official-sounding word for.

During the Cold War, the United States was engaged in an arms race with the USSR. American military build-up freed up Canzukian liberals to fight the war against communism another way - by investing in social programs. They made the case that the Soviet critique of capitalism was wrong by claiming to practice a more enlightened, humane version of it. Now, the United States seems ambivalent about Canzukian economic stability, military security, and in some cases, even sovreignty. It turns out that America’s biggest incentive to protect the Canzukian experiment may have disappeared when the Soviet Union fell.

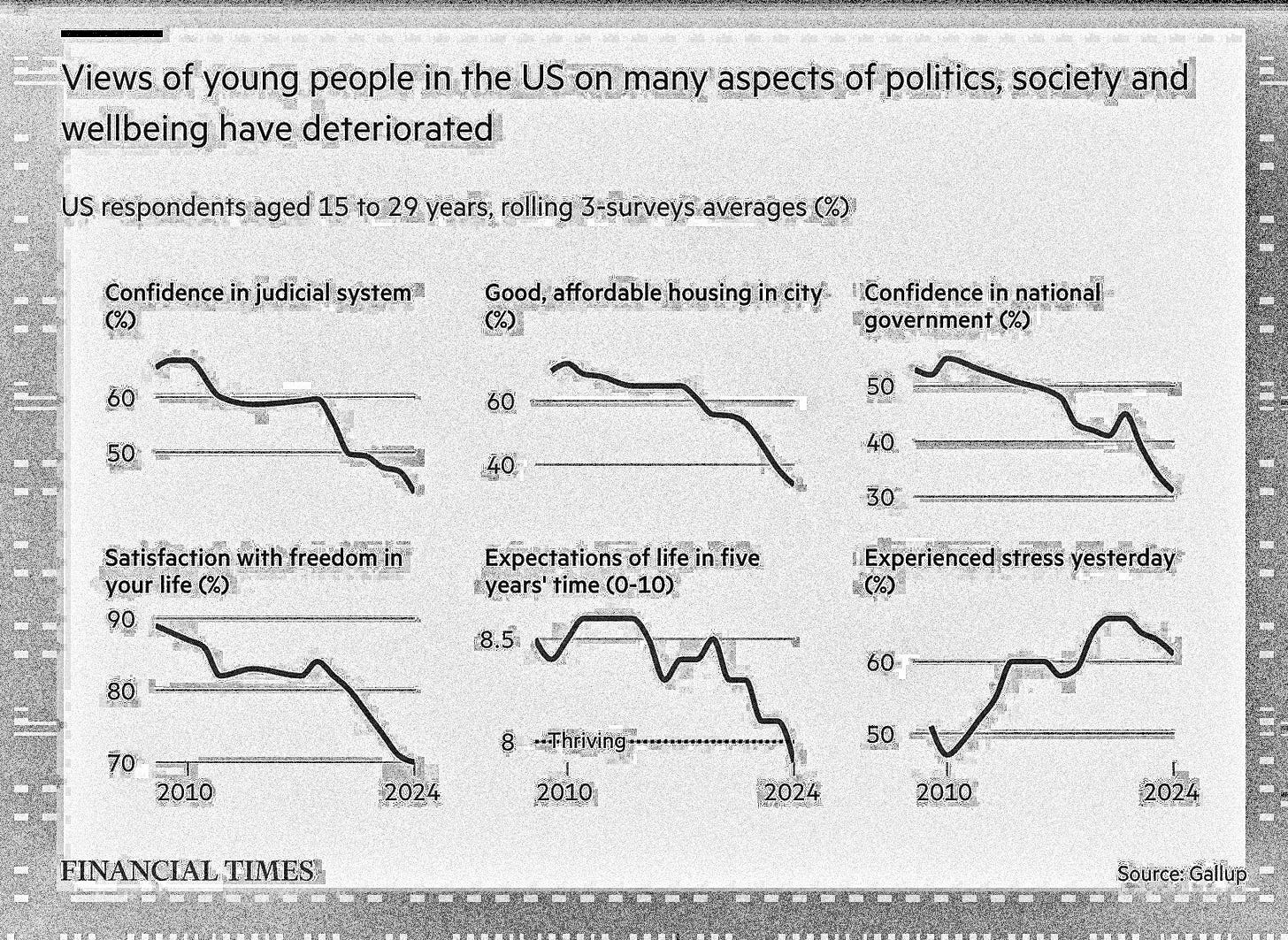

What will change in the CANZUK nations when they have to start cutting social programs in order to spend more on defense? What will change in America as the influence of post-war Canzukian liberalism disappears? How will your life change? How much of what you consider normal was the product of infrastructure that no longer exists? How much of the light in your own personal night sky is coming from stars that died before you were born? If algorithmic recommendation systems are sorting us all into “silos” or “bubbles” online, where do the other people in your bubble actually live?

II: EVERYTHING BUT RAP AND COUNTRY

The UK media environment was once very different from the one we have in America. Sometimes, as someone who grew up with an abundance of market-driven, for-profit American media, it can be difficult for me to get my head around just how different the British approach originally was. We’ve never had anything even remotely like it.

The age of broadcasting began with radio, which got started in America, in the twenties. Consequently, American broadcasting has always retained some of the market-driven, laissez-faire spirit of that era. Private companies ran the show from day one, and even after the great depression of the thirties brought the stock market plummeting back down to Earth, American broadcasting remained extremely commercial, to a much greater extent than most other countries were willing to allow. In his book Russia In The Microphone Age, historian Stephen Lovell explains:

"Although the airwaves remained in public ownership, the American licensing system brought into being a highly commercial radio culture, where advertising revenue and the consequent need to attract listeners were from an early age uppermost in broadcaster's minds. On the one hand, America could claim to have a uniquely democratic media culture, since it had few of the restrictions on broadcasters that were found in European states; on the other hand, the reality was that large corporations were from an early stage able to make enormous profits from providing access to the notionally common resource of the airwaves."

This “highly commercial radio culture” is the crucible in which pop music was originally forged. The rest of the world first encountered it as an import product from America, because no one else allowed themselves to build the kind of market-driven media ecosystem that pop music needed in order to evolve naturally.

Bob Stanley, of the UK indie pop group Saint Etienne, wrote about the relationship between pop music and advertising in Yeah Yeah Yeah, his book about the history of pop. "As catchy jingles became more prevalent, the records between them began to sound similarly perky," he wrote. "Teresa Brewer's "Music Music Music," the first US number one of the fifties, could have worked out just as well if it had been used as a Lucky Strike jingle. In other words, the jingles drove radio; records were largely there to fill the space in between."

In Britain, the BBC was explicitly designed to be the complete antithesis of the American approach. Instead of a gaggle of commercial enterprises competing for dominance over the airwaves, there would be just one non-profit corporation with a total monopoly on broadcasting everywhere in the country. Programming would be created in-house and funded by a license fee collected by representatives who went door-to-door, which is how subscriptions worked in those days.

The BBC ran no ads, faced no competition, and offered no alternative. The stated goal of the corporation was to finance and distribute works of art that could never have been made in an America-style market-driven media environment. In an official BBC handbook from nineteen twenty-eight, Director-General John Reith wrote about how the power of the new medium of radio came with a responsibility to use it for the common good. To expose the audience to “challenging new works” and to “popularise - as only this peculiar medium can popularise” the sort of music that “a concert organization run for local profit” would never be able to make money on. It was as if PBS was the only channel available anywhere in the country.

It’s appealing to see the world in terms of yin and yang, opposing forces that must be balanced and brought into harmony with one another. To an American consumer, there’s no downside to having more options. The ideal situation, to such a person, probably seems like it would have to be a balance between public and private, between art and entertainment. The best bits of both mixed up into a fun little cocktail. An endless buffet of international dishes you can sample or discard at your leisure. The architects of the BBC felt differently. They believed their aims were incompatible with those of the commercial entities that dominated media in the United States.

The monopoly was the work of people who believed that they had to force the other side off of the air entirely in order to truly succeed. Radio dramas wouldn’t be able to capture the public’s imagination if they were constantly being interrupted by ads for candy and cigarettes. The majesty of classical music couldn’t be properly appreciated by listeners who were still distracted by the catchy jingles they heard only minutes prior. The profit motive had to be completely removed from cultural production. This was a mainstream view in Britain for decades.

Even outside Britain, the BBC wielded tremendous influence. Their programming helped define the scope of what was possible in media in the anglosphere, not just for the audience, but for the professionals who learned their craft working in the British media environment. Even commercial, for-profit productions ended up being shaped in various ways by the culture that developed under the monopoly’s protection. The mere existence of such institutions in the English-speaking world had an impact above and apart from the content of their programming.

Do you have trouble focusing at length? Has the constant hum of notifications coming from your phone started to interfere with your ability to pay attention to anything else? Are you addicted to constant small hits of dopamine? The architects of the BBC were worried about what market incentives would do to our brains from the moment they were first asked to consider the implications of electronic mass media. In a way, the BBC monopoly was there to protect the public from our current reality. In exchange, the public had to endure a kind of cultural austerity. No commercials meant no pop music. No competition meant no novelty. No alternatives meant no bespoke, individualized consumption. This was normal, once.

Over time, however, the BBC’s monopoly power did diminish. One notable episode in the corporation’s evolution was the pirate radio boom of the sixties. The BBC’s radio offerings didn’t feature much pop music back then, preferring to focus on more traditional content like radio plays and news reports. Pirate radio stations stepped in to fill the gap in the market. The British teenagers of the post-war era comprised most of the audience for pirate radio, and they were quite unlike the generations that preceded them. Their childhoods weren’t swallowed up by war and austerity in the same way, and they had more pocket money. In The British Counter-Culture, 1966-73, Elizabeth Nelson described them as “newly enfranchised, in an economic sense.”

Allowing for the fall in the value of money, real earnings of teenagers in 1957 (as compared with 1938, had increased by 50 percent, which was double the rate of expansion for adults… Such increased wages and spending power on the part of youth may well account for some of the hostility felt towards them by their elders, who did not enjoy the fruits of affluence to such an extent, and had coped with the austerity of the war and postwar years.

What British teenagers loved to spend their money on most of all was products from America - movie tickets, record players, and seven inch pop singles being chief among them. American private industry, especially record companies, desperately wanted more direct access to the British audience, and they all viewed the BBC’s non-profit, ad-free, public service-focused model as an obstacle. The corporation’s unique structure left the BBC with no incentive to give in to these companies’ demands.

Libertarians within Britain shared American record companies’ disdain for the monopoly. Together, they hoped to harness the broad appeal of American pop culture in an effort to turn the British public against their own institutions. They were inspired by Radio Free Europe, a United States-led effort to broadcast propaganda ino the Soviet Union from transmitters on the capitalist side of the Iron Curtain. They wanted to undermine Western socialism using the exact same tactics that the Americans were using to undermine Soviet cultural production. From a libertarian perspective, it was all one war - a struggle of individuals against collectivism.

The first such individual to succeed in this endeavor was Leonard Plugge, a Conservative MP who brought American-style pop music and jingles into Britain through partnerships with foreign stations like Radio Normandy and Radio Luxembourg. He was so infamous for taking bribes from American record labels that even today, the practice of promoting a record to radio is still called “plugging” in his honor.

After the war, Radio Luxembourg broke with Plugge, but continued to produce commercial broadcasts aimed at British listeners. In so doing, they became the first pirate station to develop a significant audience. Broadcasts could only be picked up in Britain at night, but as transistor radios got progressively smaller and more portable, listeners had an easier time picking up the signal while listening under the covers. Radio Lux pumped American-style commercial radio directly into the ear drums of the “newly enfranchised” British teenagers of the post-war era. Teenagers like John Lennon and Keith Richards, who both report having heard Elvis Presley for the first time on one of Radio Lux’s illicit nighttime broadcasts. Pete Shotton, a childhood friend of Lennon’s, recalled those days in his memoir:

“We all regarded the States, in those days, not only as the leader of the Western World, but also as a remote, mythical place--almost a fantasyland. Since nobody we knew had ever traveled there, our impressions of the country were drawn largely from Hollywood--especially westerns and gangster films--and from such archetypally American exports as blue jeans and Coca-Cola. All the evidence convinced us that the USA was a futuristic paradise of fast cars, fast food, fast money, and fast women--a society infinitely more permissive and exciting than our own."

After the success of Radio Luxembourg established that there was an audience for commercial radio in Britain, the sixties pirate radio boom really kicked off in earnest, instigated by a man named Oliver Smedley. He was a self-described “individualist” who helped found the Institute of Economic Affairs, the most influential neoliberal think thank in history. In nineteen sixty-four, he kicked off a national furor when he started setting up new commercial radio stations on boats anchored in international waters - literal pirate ships. He wanted to fight the BBC monopoly using exactly the same tactics that the United States was using to undermine the USSR. American record labels, UK tabloids, and Seventh-Day Adventist broadcasters all funded the effort by buying airtime for ads.

Pirate stations like Radio Atlanta and Radio Caroline were deliberately trying to get the nation’s teenagers hooked on American pop culture in the specific hope that it would radicalize them against the BBC monopoly and inspire them to demand a market-driven media ecosystem like America’s. Long-term, this would help the libertarian right to undo the socialist gains of the post-war era and return to something more laissez-faire. Tony Benn, who was basically his generation’s equivalent to Jeremy Corbyn or Bernie Sanders, was public enemy number one to the pirates. DJs on Radio Caroline reportedly used to shout “Don’t Vote Labour” on the air so often that it became something like an unofficial slogan for the station.

In order to placate teenage pirate radio listeners and prevent them from becoming fully disenfranchised, the BBC offered a compromise in the form of a brand new pop station called Radio 1. Unlike the “BBC Light Programme” that preceded it, Radio 1 was devoted entirely to popular music. The best DJs from the pirate ecosystem were hastily recruited, and listeners were soon tuning in to legal, ad-free sets of contemporary popular music all day long, for the first time ever.

During the day, Radio 1 offered the kind of light, personality-driven programming you’d expect from a drive time morning show on a U.S. FM station. At night, DJs were encouraged to be more adventurous, in order to fulfill the BBC’s mandate of offering programming that goes above and beyond what a profit-driven network would be capable of. That’s when John Peel would mix grindcore and post-punk curveballs into his sets, turning the nation’s only pop station into a platform for niche underground scenes. “Numbers by day, reptuation at night” was the station’s unofficial motto, and a succinct explanation of the compromise it offered listeners.

The libertarian activists who started the pirate radio boom specifically hoped to foment a revolution against collectivism in Britain. Eventually, they got their wish. Margaret Thatcher, who became Prime Minister in nineteen seventy-eight, came from exactly the same intellectual tradition as those activists. Once in office, she wrote to the head of the Institute of Economic Affairs, the neoliberal think tank that Oliver Smedley helped found, and thanked them for helping to “create the intellectual climate” that made her victory possible.

The downfall of higher education began immediately. Back in the post-war era, the Education Act of Nineteen Sixty-Two made university effectively tuition-free in Britain. Students’ cost of living was even covered by what were called “maintenance grants.” Can you imagine? You would finish high school, apply to university or art school, and then you would spend the next four years focused entirely on education. You didn’t have to worry about where you were going to live, and you didn’t have to get a job to support yourself. For decades, this was normal.

Thatcher struck a mortal blow against the post-war status quo in nineteen eighty-one, when she implemented full tuition fees for international students. The move invited the British public to view immigrants as a bigger threat to social programs than big business or the libertarian right. In the end, the international students targeted by the policy were just beta-testing an early version of the future that awaited everyone else. In ninteen ninety-eight, tuition fees were implemented for all students.

The downfall of the BBC took a bit longer to play out. There were years of false starts and setbacks before Thatcher was successfully able to install a loyalist as Director-General. Long before that, though, many employees had already started proactively looking for ways to compromise with the new regime. Jobs at the BBC didn’t pay especially well, but there was fierce competition for them. This meant the corporation tended to attract lifers who were willing to fight very hard to hold on to their positions. Accordingly, the scope of what was possible in media began to narrow even before the first top-down reforms actually hit. The writing was on the wall.

The global shift from linear broadcasting to on-demand streaming was what really hammered the final nails into the monopoly’s coffin, though. The British public watches YouTube and Netflix now. They listen to music on Spotify, just like everyone else in the world. These new platforms are the ultimate pirate radio stations. Accordingly, the non-profit business model and accompanying set of incentives that used to define British media is buckling under the pressure. The last Conservative government expressed a desire to end the license fee system and force the BBC to run advertising. The next one might actually do it, if the liberals don’t change course and beat them to it. The revolution against collectivism continues.

The writer Mark Fisher was especially sensitive to these developments. He worked in education, where he could see firsthand the ways in which the socialist programs of Britain’s post-war era were being sacrificed at the altar of American-style market fundamentalism. This decline was a primary focus of his writing, especially during his early days blogging under the name “k-punk.” Unlike much of the aughts-era internet, his posts remains intact and readable in the present day. Even the arguments in the comments are still there.

Fisher was born into a world where laissez-faire true believers who viewed every part of life as a transactional exchange were a fringe minority, even on the right. In the sixties, universal access to education was a widely held value across all political denominations in Britain. It was Harold Macmillan’s Conservative government, for example, that passed the Education Act of Nineteen Sixty-Two, which made higher education free for everyone. Back then, the consensus view had been that education was too important to commodify, not just on an individual basis but a collective one.

In nineteen ninety-eight, it was the supposedly left-wing Labour Party who ended the golden age of education in Britain and implemented full tuition fees for all students. During the post-war era, Labour nationalized entire industries and provided universal health care that was free at the point of use. In their original manifesto from nineteen forty-five, they described themselves as unapologetic socialists who would not permit big business the freedom to exploit and abuse workers. By the turn of the millenium, though, the world had turned upside down. The existential threat of Soviet communism had been extinguished, and Labour cosequently experienced a profound change of heart, adopting many Conservative positions.

Later in life, Thatcher would claim Labour’s rightward pivot as her greatest achievement. “We forced our opponents to change their minds,” she reportedly bragged at an event. The residual traces of post-war socialism that remained in the British education system were the only reason Fisher even had a job, and even then, his whole practice as an educator was functionally just an inefficient use of resources that would inevitably be streamlined out of existence by cost-cutting technocrats. Did he have a career, or was he just Bruce Willis from The Sixth Sense, a ghost who continues to show up for work every day because it doesn’t know what else to do?

John Lennon credits Elvis Presley for inspiring him to leave home and start playing music, but it was Britain’s post-war consensus that provided him with material security and the option to study at the Liverpool College of Art. Most of the peers that would later help him launch the British Invasion were also students. Mick Jagger first met Keith Richards at a train station en route to the London School of Economics. Without the steady, uninterrupted supply of materially secure art students that post-war social programs generated, would any of the music even have happened? Would there have been anyone in the audience to see it if it did?

What if every participant in that scene had all been required to get jobs as soon as they finished high school? What if it had been necessary for them to spend more than one afternoon worrying about housing? Did their romantic, distorted view of American pop culture ever cause them to take these benefits for granted? From a certain point of view, doesn’t the predominantly individualistic, America-centric character of the sixties UK youth culture seem more aligned with Thatcherism than socialism? Was it not, after all, the teenage Elvis fans of Lennon’s era that eventually voted Thatcher into office, again and again for over a decade?

For his part, Mark Fisher cared much more about the BBC than the Beatles. He was fond of insisting that the work of Delia Derbyshire, an electronic music pioneer who headed up the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, had rendered the sixties obsolete before they even began. He wrote prolifically on his blog about the old science fiction films he saw in his youth or caught reruns of on BBC Four. The experiences he was really keen on came from beyond the scope of what the traditional for-profit record business could provide. In the nineties, he found that the anarchic, copyright-agnostic sound of jungle felt like “the future rushing in,” but as electronic music “succumbed to the same retrospective tendencies” as everything else, that feeling started to seem increasingly out of reach.

Fisher has been described by his colleague Simon Reynolds as a “post-rave John Berger.” John Berger was a Marxist art critic who was best known for “Ways of Seeing,” a documentary that aired on the BBC in nineteen seventy-two. I say “documentary,” but depending on your perspective, the more illustrative term might be “video essay.” Berger frequently appears on-screen and speaks directly to the viewer in his efforts to encourage the audience to think more critically about art and technology. It’s a text that contemporary YouTubers still cite as formative even now.

One of Fisher’s primary fixations was the concept of “lost futures” or “alternative presents.” He thought we were all being haunted by the wreckage of what could have been. That our present-day existence was constantly being interrupted by reminders that other worlds once seemed possible. Alternative ways of organizing society that used to appear viable enough to frighten the powers that be into buying our loyalty. In one of Fisher’s alternative presents, it’s not hard to imagine that he might have ended up explaining breakbeat jungle records to BBC viewers the way that Berger once explained paintings and photographs. From a distance, it sometimes looks to me like that was the job he spent his whole life getting ready for. In the end, it never materialized.

In Britain, theater has been a central part of the national culture going all the way back to the medieval period, when Shakespeare was active. The dramatic arts are a much bigger part of UK public school curriculums. Institutions like the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company receive significant public funding, while their American counterparts are forced to rely on private donations. Last year, theaters in London’s West End even sold more overall tickets than theaters on Broadway in New York City, despite the UK being a much smaller country.

This robust theatrical tradition helps keep British actors busy between film jobs, giving them opportunities to hone and improve their craft without having to wait for opportunities to do it on set. American actors, on the other hand, take other kinds of jobs to stay solvent between film and television gigs. “If I wanted to take a six-month break, I don’t have income to cover that,” American actress Sydney Sweeney recently told The Hollywood Reporter. “I don’t have someone supporting me, I don’t have anyone I can turn to, to pay my bills or call for help.” Her spare time, therefore, is much more likely to be spent doing brand deals with fashion houses or appearing in commercials for soap and mayonnaise.

In Hollywood, film studios seem to value the acting chops that the British cultural ecosystem produces quite highly. Young American actors are struggling to keep up. In twenty fifteen, the American actor Michael Douglas spoke at length about this trend in an interview with Entertainment Weekly:

The issue I hear from casting agents is that young American actors now are very self-conscious of their image. So rather than playing truthful and themselves—it might be because of so much cable, so much stuff on the internet—they’re almost kind of capturing an image of what they think they should be, rather than playing it.

Another example I have: Wall Street II and Solitary Man, each of which called for a “New York City sophisticated 17-19 year old, somewhat spoiled, wealthy girl.” Once again, we ended up with Imogen Poots and Carey Mulligan, two British actresses playing pretty American roles. So it is an issue, and I speak about it a lot. It’s certainly commendable to what’s going on in the U.K., and I think a lot of that has to do with how London works both—you can jump fairly easily from television to movies to theater. And also, as young British actors, they know American films are still your worldwide platform, that they have to learn an American accent. So it’s relatively effortless for them. And then they happen to be pretty well-trained, disciplined actors, not concerned about their images as to just playing the role and the part.

In America, young actors begin considering the market value of their actions the moment they enter the field. There’s never a point where they’re able to see their artistic practice as separate from how they make a living, so they struggle to let go of material concerns and disappear into a role. The advent of the streaming economy, which doesn’t offer actors the long-term security that residuals used to provide in the era of linear broadcasting, has foregrounded financial concerns more than ever.

Trained by social media analytics as much as by any institution, American actors are incentivized to see advertising as their primary art form. They make creative decisions based on what kind of brand deals they’re looking to pursue, approaching the craft like true small business owners. British actors, on the other hand, are incentivized to focus on suppressing their natural accents and mannerisms in order to completely inhabit the character they’re playing. They can compartmentalize their own concerns in the service of an employer.

Hollywood studios have therefore come to rely heavily on British actors when staffing up character-driven productions, whether they’re tentpoles or awards season prestige plays. Spider-Man’s a British guy. Superman’s a British guy, too. Batman is British. Martin Luther King Jr. is British. Daniel Day-Lewis is Abraham Lincoln. Clive Owen is William Jefferson Clinton. Colin Farrell is James Gandolfini. Daniel Craig is Foghorn Leghorn. Casting directors would really be in a pickle if they ever lost access to their supply of these folks.

I’m a millennial, so this kind of cultural offshoring is what I’m used to. In fact, I’m used to seeing much more potent forms of it. British celebrities used to be famous in America for things other than just their ability to fit seamlessly into our films and TV shows. When I lived in the American midwest during the aughts, the impression I got was that being a hipster was at least as much about thinking the UK version of The Office was better than the American remake as it was about drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon or parting you hair on the side.

I remember regularly seeing people walking around just casually sporting Union Jacks, as if to project dissatisfaction with George W. Bush’s America by pledging allegiance to Skins and Harry Potter instead. Remember André 3000’s clothing line, Benjamin Bixby? What about the Decemberists, the indie band from Portland that became a successful national touring act by dressing like characters from a Charles Dickens novel? When nu-metal fell out of fashion, Limp Bizkit frontman Fred Durst’s best ideas about how to get people to start liking him again revolved around covering The Who and getting paparazzi to photograph him wearing a Smiths T-shirt.

In Minneapolis, the city where I spent my twenties, the ultimate prize local bands could win if they generated enough buzz around town was a record contract with a venerable UK indie label like Domino or Rough Trade. One such band was Howler, who went from busking at farmer’s markets to appearing on the cover of the NME in little over a year. Their singer dated Johnny Marr’s daughter for a little while and their debut album was called America Give Up. Anglophilia was rampant!

Back then, a lot of the most popular dance nights for people in my age group were so-called “eighties nights” that it would have been more accurate to describe as “anglophile nights.” Musically, these parties felt like celebrations of an era where UK new wave occupied a more dominant position in the mainstream than American hip-hop or R&B. Those were the days when people used to say “I listen to everything but rap and country.” From a certain point of view, one could argue they might as well have been saying “I listen to everything but American music.”

In recent years, though, the trend has completely reversed itself. Beyoncé and Post Malone have both dropped country records, Morgan Wallen and Shaboozey have both broken chart records, and new releases by formerly dominant transatlanticist pop stars like Dua Lipa have been disappearing from the charts in record time. Nine-time Gathering of the Juggalos attendee Jelly Roll is suddenly on his way to being a household name after twenty years of toiling in the hick-hop trenches. Missouri-born singer/songwriter Chappell Roan languished on her label’s back burner for years waiting for an opening like this. It seems like the mainstream audience wanted this moment to happen just as badly as she did.

Taylor Swift’s career began during the aughts, when anglophilia was much more commonplace. Like many of her fans, she’s clocked serious hours on Tumblr, a platform whose American userbase is infamously fixated on BBC shows like Sherlock and Doctor Who. Unlike those users, Taylor Swift is a real life celebrity who was able to leverage her power to compel the guy who plays Loki in the Avengers movies to walk around in public sporting an “I Heart T.S.” tank top. If anglophilia had a leaderboard, she would have to rank near the top.

In recent years, though, her predilection towards UK cultural products left her vulnerable to some of the most intense backlash of her career. She seemed completely blindsided by the reaction she faced from fans in the States after she hard-launched a public relationship with Matty Healy of The 1975, an extremely British man who became quite famous in his home country after realizing that LCD Soundsystem’s “All My Friends” would have been a much bigger hit had it been made by a bunch of guys in their twenties. A sizeable chunk of Swift’s fanbase went into open revolt until she made the clutch decision to swap Healy out for an American NFL player.

An observable surge of interest from zoomers in “shoegaze” might seem like evidence that Canzukian cultural production is not yet down for the count, but then you start paying attention and realize that by “shoegaze,” these kids mean American indie bands like Beach House and Title Fight. Another big buzzword is “midwest emo,” which effectively just seems to mean “American-sounding rock music,” even when the Brits are doing it. American music is what everyone listens to everywhere now.

The BBC monopoly of old might have more in common with the “Great Firewall” that insulates the Chinese internet from the rest of the world than it does with cultural production in the contemporary anglosphere. Alternative approaches that once looked viable or even desirable are now considered heretical in our current geopolitical reality. Was the monopoly authoritarian? Is authoritarianism ever justified?

This past weekend, at the nationwide “Hands Off!” protests, I watched scores of American liberals take to the streets in protest of the influence that a particularly powerful CEO is exerting over the government. Would they be interested in something more like the Chinese system, where power-tripping CEOs get crushed by the state? I suspect the question would just make them uncomfortable. They might want alternatives, but they’re not willing to risk being on the wrong side of the next Iron Curtain. Most of them are boomers, after all. They remember what happened the last time the United States felt threatened by the competition.

What feels normal and comfortable to you? Which version of reality strikes you as the most correct? How much longer is what feels normal to you still going to be possible? Are you already being haunted by a future that never was?

III: ARE YOU A POPTIMIST?

When I started reading k-punk, I wasn’t in a position to understand most of it. I was twenty years old and living in the United States. I didn’t know who John Berger was, and my only experience with the BBC Radiophonic Workshop was hearing a couple seconds of the Doctor Who theme once or twice on public television before immediately changing the channel. Most of the government policies and cultural artifacts that mattered so much to Mark Fisher were indecipherable to me. I wasn’t there for any of that. I just wanted to watch him rant about pop music.

I wasn’t alone, even back then. One comment, left in January of two thousand and four by a reader who identified himself as “luke,” perfectly encapsulated the relationship that young and/or American readers like me had with the blog. “Hooray,” he wrote. “this is what I want from mark k-punk, real ideas, vigorous writing, contrarian standpoint, not more nostalgia stuff about 70s tv shows.”

As a music critic, Fisher definitely came off as contrarian. Back in those days, he couldn’t have been more out of step with the prevailing trends, and he seemed to know it. Later in two thousand four, Pitchfork announced a revamped track review section and a new focus on producer-driven music from the worlds of rap, pop, and R&B. Not long after that, New York Times music critic Kelefa Sanneh published “The Rap Against Rockism,” a polemic that painted critics as being too hopelessly in thrall to the norms and conventions of the rock era to appreciate what modern rappers and producers were accomplishing in the studio. Fisher, on the other hand, was posting remorselessly about how Timbaland was washed and hadn’t done any truly vital work in at least six years.

In a post from January of two thousand four entitled “Fed Up of Hip Hop,” he laid out one of his favorite arguments, which he continued to workshop in blog posts and columns in the New Statesman in the years that followed.

Dare it be admitted, but isn't Hip Hop the problem these days?

Hip hop is now totally assimilated; not so much a part of the mainstream, as the mainstream itself, Pop's Reality (Principle). There's nothing unsettling about it any more. On the contrary: hip hop is quotidian, everyday. It's everything you'd want to escape from…

If you are looking for the 00's equivalent of 70's rock dinosaurs, look no further than Jay-Z, Pharell and their kin. Like those lumbering beasts of three decades ago, they are living off the sonic invention of the previous decade, complacently assuming that they still occupy the avant-garde.

The song that prompted this tirade was “Milkshake” by Kelis, which should explain a lot about why Fisher’s music writing isn’t what eventually broke him through to a larger audience. I think sometimes he was overly keen to see pop music as evidence of the rot that had infected institutions like the BBC and the British education system he worked in. I think he wanted to convince the readers who showed up looking for music takes that his seventies nostalgia wasn’t some isolated, individualized problem that only affected him. To Fisher, it was all one story, and he was perfectly willing to risk looking stupid in public in order to get that message across.

If he were still alive today, though, he would come across as much less of an outlier. Jay-Z and Pharrell really are oppressive dinosaurs now. Triplet flows and 808 drums have been fully absorbed into the sound of advertising, forcing A-list artists to pivot to acoustic guitars and twang in order to protect their reputations as credible, prestigious luxury brands. Major labels spent last year liquidating employees who specialized in hip-hop, convinced that generative AI models will soon contain all the cultural expertise they’ll ever need. If they’re wrong, they’ll just hire some of the same people back and pay them less money for more work. Why not? Who will stop it?

In Britain, some of the most urgent commentary on the current-day music scene comes from a mononymous writer and DJ known as Elijah, who chronicles British radio’s startling lack of interest in British music on social media. BBC’s Radio 1xtra, a digital station that once focused primarily on homegrown scenes like Grime, Garage, and Drum’n’bass, is now much more likely to play C-list American rap hits from the aughts like Joe Budden’s “Pump It Up.” Back in the early eighties, when a few upstart post-punk bands and music writers in the UK started complaining about “rockism,” their primary issue was that BBC Radio 1 was playing too many seventies dinosaurs and not enough young bands. Now, the young UK upstarts following Elijah’s commentary on Instagram likely feel exactly the same way about American rappers and pop stars.

Last year, in fact, most of the music on the overall UK singles chart was the same music that was on the Billboard Hot 100 in America. Not one of the Top 10 highest-selling singles of the year was released by a UK artist, which means that country songs by Dasha and Shaboozey made a bigger splash in Britain than anything going on domestically. Not long ago, Taylor Swift was risking everything to escape being pigeonholed as a country artist so she could broaden her appeal to international audiences. Now, it’s not difficult to imagine a world in which UK artists feel pressured to start affecting twangy accents and sucking on Zyn pouches in order to seem more American.

So, basically, we’re living in Mark Fisher’s worst nightmare. The distinctive non-profit British media environment that he so cherished has been eaten away by Thatcherite reforms and data-driven, hyper-efficient competition from streaming. What dominates Britain now is American exports, and what’s next is generative AI. Automated, individualized cultural production that is incapable of imagining anything new. A machine that exists to turn all other possible futures into lost ones that can only be consumed as content. The “weird” and “eerie” aesthetics of Fisher’s favorite niche cultural artifacts gobbled up by data centers and repackaged as a stack of cooldown timers and recurring subscriptions to be consumed in isolation by depressed introverts.

Maybe that’s why Fisher’s work has continued to find an audience, even amongst young Americans, who presumably have little firsthand experience with the specific institutions he mourned and celebrated. Maybe they can feel the secondary impact of such decline in unexpected ways. Maybe some of us were depending on those institutions to a greater extent than we were consciously aware of, and we didn’t even realize how reliant we were until they started to go away.

One of Fisher’s favorite subjects to complain about on k-punk was the “enlightened connoisseurship” of people he called “poptimists.” His beef wasn’t with pop music, though. He admitted in a post entitled “Why I Hate Kylie” that he enjoyed “Can’t Get You Out Of My Head” as much as anyone. If anything, his blog posts about how rap was boring because it functioned as “an ultra-masculinist refusal of glam’s feminizing threat” would probably register as stan-adjacent to much of the commentariat if he were still making them now.

In fact, Fisher seemed to have a somewhat romantic view of what he described as “the ups and downs, the expectations and the disappointments [that] are part of the masochistic reel/real of being a popfan.” At least the pop stan worldview allows for the possibility of flop eras and outright decline. It contains language that is capable of describing, on some level, problems that are systemic rather than merely individual in nature. That’s workable. What bothered Fisher the most was the “you can always find a good record if you look for it” types. “Poptimists,” in Fisher’s view, are the ones who always insist there’s no such thing as a bad year for music as long as you’re willing to dig. The cardinal sin was not pop, but optimism.

In the comments section underneath a k-punk post from two thousand four, the writer Tom Ewing made the case for the poptimist position. He described a moment in two thousand two, when he was “sitting in the car, flicking between channels” and came across “five or six different songs from completely different scenes” that “all sounded fantastic.” “It is a position that suits older armchair listeners more than young firebrands, I'm not apologising for that.” he wrote. “At its extreme [the poptimist position is] a very detached, solipsistic way of listening.”

“One of the really key things for me,” he continued. “Is the feeling that thanks to technology you don't have to dig or search hard at all for the great music - now at the moment there's still an affordability gap because you need a PC to run file-sharers, get tunes etc. but in a couple of years that intermediary won't be needed I'm guessing. And then all you need is a way of finding out about new songs and you need never want for good music again? Utopia, huh?”

What about you? Are you a poptimist? Today, the “detached, solipsistic way of listening” that Ewing described back in the aughts has become the dominant mode of consumption. Does this feel like utopia to you?

Recently, on an episode of the Panic World podcast, the writer Ryan Broderick and Chapo Trap House co-host Felix Biederman discussed the broader cultural implications of Trump’s electoral victory last November. Towards the end of their conversation, Broderick shared a particular theory he wanted Biederman’s take on.

He suggested that “the banning of Trump from mainstream social media” after the January sixth riots “forced him to change his behavior online in a way that made him more prepared for the future we were all heading towards.” Basically, Broderick argued, “we exiled him from the city out into the woods, without realizing the city was burning down behind us and we’d eventually be out in the woods, too.”

“That’s incredibly interesting,” Biederman said in response, his enthusiasm picking up as he plugged in some of his own conclusions. Referencing cutscene dialogue from the Metal Gear Solid series, he described the current media landscape as a “war economy” - a “highly mercenary environment where no one man, one show, or even one media concern will control a majority.” Being forced out of the mainstream and into such an environment, where Trump had to rely on “manosphere” podcasters and fringe commentators like Nick Fuentes, may have helped him overcome the declining power of the traditional media establishment that was backing Biden.

Broderick himself was “exiled from the city out into the woods” back in twenty twenty, when he was fired from BuzzFeeed News over concerns about plagiarism. A few years later, BuzzFeed shuttered their entire news operation in order to pursue a new focus on AI-generated content - effectively making the offense Broderick got fired for a core part of their business model going forward. What initially looked like a career setback may have been more of an opportunity. Being forced to compete in the “war economy” of Patreon tiers and newsletter subscriptions a little earlier than everyone else might have put Broderick in a better position than he would have been in had he stayed a gainfully employed member of the doomed traditional media establishment for another couple of years.

Not long after his conversation with Biederman, Broderick fleshed out his thesis further in an installment of his newsletter. Borrowing terminology from Biederman, he outlined a struggle between two opposing forces that he described as “Article World” and “Post World.”

As [Biederman] sees it, “Article World” is the universe of American corporate journalism and punditry that, well, basically held up liberal democracy in this country since the invention of the radio. And “Post World” is everything the internet has allowed to flourish since the invention of the smartphone — YouTubers, streamers, influencers, conspiracy theorists, random trolls, bloggers, and, of course, podcasters. And now huge publications and news channels are finally noticing that Article World, with all its money and resources and prestige, has been reduced to competing with random posts that both voters and government officials happen to see online. These features are not just asking, “what happened to American men?” They’re asking, “why can’t we influence American men the way we used to?”

Jay Caspian Kang is a staff writer at The New Yorker, which must surely be one of Article World’s flagship publications. In a series of tweets sent on March twenty-fifth, he seemed to reinforce Broderick’s characterization of Article World as a city that’s burning down, forcing scores of refugees to venture out into the wilderness of Post World. “Never been more convinced the future of the Democratic Party is far outside the current mainstream media discourse,” he wrote. “We are dudes yelling on forums while the rest of the country has moved to Facebook. And I’m not sure we know it yet.”

What exactly caused this shift? Who started the fire that burned Article World down? Writing in his newsletter, Broderick didn’t seem sure himself.

Maybe it was the pandemic, maybe it was the insurrection, maybe it was the fact publications like Vanity Fair were still paying writers six figures AN ARTICLE!!! up until the mid-2010s while they were being devoured by social platforms. But Article World is dying, or maybe already dead, and Post World is ascendant. And it’s not just a political problem. It’s impacting music, fashion, celebrity, law, economics — I could go on and on here. We’ve replaced the largely one-way street of mass media with not even just a two-way street of mass media and the internet, like we had in the 2010s, but an infinitely expanding intersection of cars that all think they have the right of way. Think about it for a second. When was the last time you truly felt consensus?

As a Canadian-American, here’s my perspective.

During the Cold War era, I think the infrastructure necessary to produce “consensus,” as well as other products like “the monoculture” and “liberal soft power,” existed primarily outside the United States, in countries like Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. As long as these smaller, more homogenous countries enjoyed American military protection, they could afford to invest deeply in education, social programs, and domestic cultural production. American liberals in particular, I think, became very reliant on these countries for cultural and political leadership.

On a consumer level, that meant anglophilia. “Enlightened,” “poptimist” connoisseurs developed a taste for products that came out of Canzukian media environments, and for the alternative models for cultural production that existed in those countries. Politically, it meant seeing Canzukian liberals like Justin Trudeau, Jacinda Ardern, and Tony Blair as role models. It meant allowing center-left parties in countries with wildly different cultures, histories, and demographics to define the scope of what was possible for liberalism in America.

We saw this very clearly during Barack Obama’s presidency. His election carried incredible historical significance, but he was also the same kind of sleek, sophisticated, cosmopolitan public figure that tended to lead center-left parties in CANZUK. Part of the sales pitch that got American liberals to embrace Obama en masse was a fantasy about how impressed the rest of the world was going to be when we finally elected someone who looks, acts, and talks like a real world leader. A big part of the Obama coalition primarily seemed to want their own Justin Trudeau.

By the time Obama was elected, Canzukian cultural production had already been in decline for some time, though. The Soviet Union had been gone for almost twenty years. The West’s incentive to win the argument against communism with a more humane, enlightened form of capitalism had vanished. The drive to build a government that works for the good of all people had already been replaced by a drive to privatize and deregulate. Rent was going up, while wages stayed low. All things being equal, anglophilia should have been on the wane.

Paradoxically, though, as broadband brought more and more Americans online, CANZUK cultural products became more accessible than ever before. As an American consumer with an internet connection, I suddenly had access to an entire universe of films, TV shows, and musical recordings that would have qualified as “rare” or “obscure” only years earlier. Writers like Mark Fisher, who were obscure even in their own countries, could become a bigger part of my daily life than anyone writing for local publications. Intercontinental communication became so cheap that the discourse felt rich even when everyone participating was broke.

In the old days, when a business would burn down unexpectedly, the owners would try to sell off whatever fire-damaged merchandise remained at the steepest possible discount. That’s where the term “fire sale” comes from. A fire sale might bring about the biggest single-day sales totals in the history of a particular business, but it’s also the end of the story. The low prices necessary to bring in so many eager buyers aren’t sustainable. They only make sense when it’s time to cut your losses and move on.

I think the anglophilia boom I witnessed in the aughts was kind of like a big fire sale. Millennials cheerfully sifted through the accumulated treasures of the post-war anglosphere and picked out bargains to acquire at the deepest possible discount. Once the shelves were empty, though, they stayed that way. The temporary digital ubiquity of Canzukian cultural exports obscured the decline of the infrastructure that produced them in the first place. It was an explosion of soft power so bright and so dazzling that it look a long time for the audience’s eyes to adjust and register the size of the crater it left behind. The spectacle mystified the underlying material relations.

Canzukian liberalism has therefore been kind of a Wizard of Oz situation for some time now. As these nations continue to spend less on education, and less on protecting domestic cultural production from market forces, liberal soft power will continue to decline throughout the anglosphere. Behind all of the vaunted prestige and authority and history of “Article World,” “the monoculture,” “post-war liberalism,” or whatever you want to call it, there is now usually just a skeleton crew doing whatever it takes to keep the lights on. Once, there was power behind the prestige. Numbers and reputation. Those days are gone. We can all see that now, right?

In his book Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan maintained that for millions of years, human beings relied more on our ears to help us understand the world than our eyes. Culture and history were transmitted orally, for example, not through the written word. That all changed with the invention of the printing press. Books effectively uprooted us from the “acoustic world” that we perceived with our ears and inducted us into a new “typographic” visual culture of reading and writing.

Even just the sight of ordered, uniform letters, evenly spaced against a blank background, would have been totally unlike anything humanity had ever experienced before. Literacy introduced humans to a level of continuity, uniformity, and linearity that just did not occur naturally in the acoustic world. The process of understanding such glyphs and deriving meaning from them might have shaped us much more significantly than any of the actual ideas or information being transmitted. The medium is the message, and so on.

In the early aughts, I feel like I kind of got uprooted into the typographic world of the text-based internet. Very much in keeping with McLuhan’s characterization of technology as an extension of the human body, I used to keep my MacBook on my person at all times, as if it were an essential organ that I needed in order to stay alive. My social life accordingly revolved much more around language than geography. I had typographic friends and enemies all over the globe, but would sometimes go entire days without speaking a single word out loud to anyone in the acoustic world. I wanted to live in Article World so bad that I couldn’t see it was dying. The internet made the culture of the post-war era so accessible that I didn’t realize the extent to which it had ended.

Elsewhere in Understanding Media, McLuhan suggested that the antithesis of the printing press is radio. Books prompt us to use our eyes, which inducts us into the visual, typographic culture of reading and writing. Radio, on the other hand, compels us to look up from what we’re reading and start using our ears to perceive the world instead. He described radio as a “tribal drum” that reverses “the entire meaning and direction of literate Western civilization.”

Compared to reading, radio is an immersive, participatory, emotionally charged sensory experience that many people share. In an environment where this sort of media is dominant, these shared sensory experiences bond people to one another rather than shared knowledge or shared values. The experience of radio, and presumably also the experience of listening to podcast clips with one’s phone on speaker, compels us to “retribalize.” To start thinking and behaving more like we did in the oral cultures of the acoustic world, before literacy made us into typographic creatures.

Since the aughts, the internet has been getting progressively less typographic. People actually use the speakers in their phones now. Scrolling through video-based social media platforms feels more like turning the dial on a radio receiver than reading a book. Forums and instant messaging platforms that brought users from all over the world through the unifying power of text have been replaced by new platforms.

There are location-based dating and hookup apps. There is location-based ad targeting that follows you around wherever you go online. There are location-based recommendations on platforms like TikTok, and even fully location-based platforms like Nextdoor. Furthermore, text itself is becoming a niche concern compared to audio and video content, which doesn’t depend on or promote literacy in the same way that the typographic internet of “Article World” does. If you don’t want to write out an idea, you can represent it with emojis, generated images, voice memos, photos, haptics, or videos instead. Twitter might be where news first breaks, but much of the population probably hears it second-hand on television or from podcasts and short videos. The internet is no longer typographic. It has become post-literate.

In the early twenty tens, smartphones brought the internet into the mainstream by putting access to it directly in the public’s hands. Going online was still a personal choice, though. You were free to opt out. Typographic norms stuck around despite the decline of real-world typographic infrastructure because the internet still appealed primarily to typographic thinkers. The pandemic changed that by forcing everyone online. The typographic majority that had dominated internet culture since the medium’s inception became the minority overnight.

Max Read, author of the Read Max newsletter, has written extensively about the “demonstratively macho subcultures” that have been thriving on the post-literate internet since the pandemic began. One is the “Zynternet,” a gambling and crypto-adjacent sphere of podcasters and content creators that revolves around online sports betting and disposable nicotine pouches. According to Read, the Zynternet is “broadly conservative” but not driven by the specific ideological or political agendas that animate more overtly partisan commentators like Ben Shapiro or Charlie Kirk.

Those guys are arguably the contemporary equivalent of right-wing talk radio hosts like Rush Limbaugh and Michael Savage. In some cases, the lineage is obvious and direct: Shapiro has done work for long-time talk radio fixture Dennis Prager, while Charlie Kirk is heard on the airwaves daily courtesy of the Salem Radio Network, which has also platformed shows by Steve Bannon, Hugh Hewitt, and Sebastian Gorka. The Zynternet is a new evolutionary step - a right-coded media counter-establishment capable of spitting up post-literate Howard Sterns, Ryan Seacrests, and Ellens Degeneres.

In the “war economy” of contemporary internet culture, maybe no single one of these newly-minted celebrities ever attains the kind of monocultural dominance we got used to in the old paradigm. From their perspective, that’s probably fine. The Zynternet is weeds and wildflowers. It’s blackberry bushes growing in around rusty barbed wire. It’s what develops in the absence of a broad consensus about what else ought to be built. An invasive species that has become so ubiquitous that every new generation that gets born into this world will have a harder and harder time imagining life without it.

The typographic internet of “Article World” was highly literate and international. The consensus it generated was not an American consensus - it belonged to the wider anglosphere, and was mostly produced in smaller, whiter countries with less immigration and more extensive social programs. The Zynternet is post-literate and regionally, specifically American. The business models that power it revolve around American citizens betting on American sports. Apps that make recommendations based on where the user lives. An internet that has changed radically in order to better serve the needs of casual users, not the transatlantic, typographic population of elite early adopters that used to dominate it.

As far as America is concerned, I don’t think the Zynternet is an aberration, or even necessarily a new development. I think it’s the contemporary equivalent of the commercial broadcasts that the UK pirate radio moguls of the sixties financed in order to undermine the BBC monopoly. I mean, it’s basically the contemporary equivalent of the corporate, profit-driven American media landscape of the nineteen twenties - the “ether chaos” that frightened the UK government into creating the BBC in the first place. It’s medicine shows and tent revivals. It’s the kind of culture that develops automatically in the first world when significant state power isn’t being used to enforce a different set of ideas about what media should be. It’s normal. It’s what we should expect.

Maybe the typographic culture of the post-war era was the aberration. It likely never would have existed at all if Americans hadn’t been so terrified of Stalin and Sputnik. The United States became willing to suppress and moderate its own essential nature in order to secure allies - like a squad of vampires rolling up to an afternoon pool party with full-body wetsuits and titanium umbrellas, shouting “How do you do, fellow sunbathers?” That world is gone now, and if you believe the demographers who obsess over birth rates, the eventual absorption of former allies like Canada and the United Kingdom into the United States is not just possible but likely. What looked like genuine alternatives may have just been slightly longer, more scenic routes to the same place we were all going anyway. Maybe the details don’t actually matter after all.

my god this should be a book

Fantastic as always.